With a shudder, the Amtrak Empire Builder wheezes to a stop at the Whitefish Depot as fat snowflakes drift down from the morning sky. A porter in a suit and tie helps passengers down onto the platform, where taxis and vans have appeared, into a swirl of hugs and handshakes and hoisting baggage.

That throwback charm suits Whitefish, a Montana town tucked up against the Continental Divide 130 miles north of Missoula. In summer it gears up to host the denizens headed for Glacier National Park, 25 miles east. Come winter, the town kicks back, takes a deep breath and enjoys being a very different Whitefish: a now-empty national park, a little-known ski mountain, snowy trails and an easygoing, amiable downtown. In other words, all the reasons you should visit.

TRAIN TOWN

Whitefish grew up along the tracks of the Great Northern Railway, which pushed through here in 1904 to create the nation’s northernmost transcontinental route. To build business, the rail also lobbied for the establishing of Glacier National Park, and for years provided the only access to the park and the railroad-owned hotels it constructed there.

More than a century later, Whitefish’s identity remains intertwined with those tracks. Just as a set is integral to a movie, its stately Tudor Revival depot is an essential part of its downtown, welcoming the daily arrivals of Amtrak—from Seattle every morning and Chicago every evening. It ranks as the busiest Empire Builder stop between Seattle and St. Paul, Minnesota.

It’s just a one-block stroll from the Whitefish Depot to downtown, which is laid out in tidy blocks along Central Avenue. Whitefish achieves that elusive balance of authentic town and destination: There’s still a hardware store selling snowblowers on the main street, alongside dining options and other amenities far more interesting than those you typically find in a Western town of 7,000.

SNOWY TRAILS

Whitefish takes its name from Whitefish Lake, a glacier-carved body of water that stretches nearly 7 miles north from town. Sealed under snow and ice for much of the winter, it provides a bracing venue for the annual Penguin Plunge, during the Whitefish Winter Carnival, every February. The town is surrounded by miles of trails and dirt roads to explore. The Whitefish Trail offers over 35 miles of marked trails leading to several lakes and overlooks.

At the Whitefish Bike Retreat, owner Cricket Butler has created a casual lodge on 19 wooded acres with direct access to the Whitefish Trail. Butler, who does things like race a mountain bike from Canada to Mexico in her spare time, created the lodge to serve cyclers, tricking it out with cast-off rims, sprockets and other bike parts. In winter, you can rent snowshoes on-site, or try a “fat bike,” an oversized bike frame and tires that let you roll along the snow-covered trails like a monster truck. Groomed cross-country ski trails lie right across the road too, at the Stillwater Mountain Lodge.

WHITEFISH MOUNTAIN RESORT

You can hardly miss Whitefish’s biggest winter attraction. Big Mountain rises just 8 miles north of downtown and is etched with the ski trails of Whitefish Mountain Resort. Nearly a decade of improvements has turned what was largely a locals’ mountain into a growing regional ski destination. Weekenders roll in from Missoula and Calgary; Amtrak draws passengers from Seattle and Portland, who arrive by overnight train and ride the free Ski Bus to and from town. An airport in Kalispell, 24 miles south, provides another gateway.

Skiing here certainly still feels like a local secret: Because the ski slopes are spread across more than 3,000 acres and 2,300 vertical feet, there’s plenty of terrain to go around. From the 6,817-foot summit, slopes fan out in all directions. Long intermediate trails arc down broad ridges on the south-facing “front” side, steeper runs drop into the gullies, and gentle beginner runs fan out near the base village. West-facing Hellroaring Basin provides a dedicated advanced area of chutes and steep shots through the trees. A new chairlift on the north side expands a forested amphitheater of mostly intermediate to advanced terrain that hides the resort’s driest, deepest snows.

GLACIER NATIONAL PARK

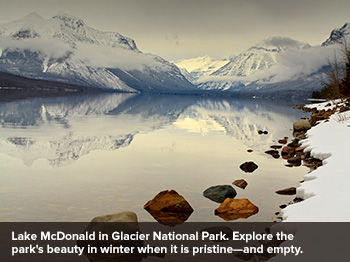

Even Big Mountain is dwarfed by the ragged spine of peaks to the east, the crest of the Continental Divide that runs through Glacier National Park. Established in 1910 as the United States’ 10th national park, Glacier encompasses more than 1 million acres of natural wonders—glacier-scoured mountains, more than 700 lakes, deep forests, rivers, waterfalls and populations of grizzly bear, gray wolf, moose, mountain lion and mountain goat.

Glacier becomes wilder in winter, when snow sometimes buries the 50-mile Going-to-the-Sun Road. Sign up for a snowshoe or ski tour with Glacier Adventure Guides. Guides customize trips to suit your interests and skill level, from a relatively flat snowshoe tromp around Lake McDonald to a 2,800-foot climb up toward Sperry Glacier or an above-tree-line ski tour along 5,220-foot Marias Pass. “In the summer the park averages 18,000 people a day,” says owner Greg Fortin. “In the winter it becomes a roadless wilderness; there might be 120 people in the entire park. It’s pristine—and it’s fun to have Glacier all to yourself.”

The Details

Whitefish Trail: 1.406.862.3880; whitefishlegacy.org

Whitefish Bike Retreat: 855 Beaver Lake Rd.; 1.406.260.0274; whitefishbikeretreat.com

Stillwater Mountain Lodge: 750 Beaver Lake Rd.; 1.406.862.7004; stillwatermtnlodge.com

Whitefish Mountain Resort: 1.406.862.2900; skiwhitefish.com

Glacier National Park: 1.406.888.7800; nps.gov

Glacier Adventure Guides: 1.877.735.9514; glacieradventureguides.com

NOTE: Information may have changed since publication. Please confirm key details before planning your trip.